Siege of Leningrad

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Siege of Leningrad, also known as the Leningrad Blockade (Russian: блокада Ленинграда, transliteration: blokada Leningrada) was a prolonged military operation by the German Army Group North and the Finnish Defence Forces to capture Leningrad in the Eastern Front theatre. It started on 8 September 1941, when the last land connection to the city was severed. Although the Soviets managed to open a narrow land corridor to the city on 18 January 1943, the total lifting took place on 27 January 1944, 872 days after it began. It was one of the longest and most destructive sieges in history and one of the most costly in terms of casualties.[8]

Contents |

Background

The capture of Leningrad was one of three strategic goals in the German plan, codenamed Operation Barbarossa for the Eastern Front. The strategy was motivated by Leningrad's political status as the former capital of Russia and the symbolic capital of the Russian Revolution, its military importance as a main base of the Soviet Baltic Fleet and its industrial strength, housing numerous arms factories.[9][10]

Hitler was so confident of capturing Leningrad that he had the invitations to the victory celebrations to be held in the city's Hotel Astoria already printed.[11]

The siege was to be laid by the Army Group North as part of Operation Barbarossa, launched on 22 June 1941 with assistance from the Finnish Defence Forces.[12] The preconditions for the siege were created by the Barbarossa in the south and the Finnish reconquest of the Karelian Isthmus from the north of the city.

Preparations

German plans

Army Group North under Field Marshal von Leeb advanced to Leningrad, its primary objective. Von Leeb's plan called for capturing the city on the move, but due to strong resistance from Soviet forces, and also Hitler's recall of 4th Panzer Group, he was forced to besiege the city after reaching the shores of Lake Ladoga, while trying to complete the encirclement and reaching the Finnish Army under Marshal Mannerheim waiting at the Svir River, east of Leningrad.[13]

Finnish military forces were located north of Leningrad, while German forces occupied territories to the south.[14] Both German and Finnish forces had the goal of encircling Leningrad and maintaining the blockade perimeter, thus cutting off all communication with the city and restricting them from getting any food or goods.[2][13][15][16][17][18]

Leningrad fortified region

On 27 June 1941 the Council of Deputies of the Leningrad administration organized "First response groups" of civilians. In the next days the entire civilian population of Leningrad was informed of the danger and over a million citizens were mobilized for the construction of fortifications. Several lines of defenses were built along the perimeter of the city, in order to repulse hostile forces approaching from north and south by means of civilian resistance.[2][5]

One of the fortifications ran from the mouth of the Luga River to Chudovo, Gatchina, Uritsk, Pulkovo and then through the Neva River. The other defense passed through Peterhof to Gatchina, Pulkovo, Kolpino and Koltushy. Another defense line against the Finns, the Karelian Fortified Region, had been maintained in the northern suburbs of Leningrad since the 1930s, and was now returned to service. A total of 190 km of timber barricades, 635 km of wire entanglements, 700 km of anti-tank ditches, 5,000 earth-and-timber emplacements and reinforced concrete weapon emplacements and 25,000 km of open trenches were constructed or excavated by civilians. Even the guns from the Aurora cruiser were moved inland on the Pulkovo Heights to the south of Leningrad.

Establishment

The 4th Panzer Group from East Prussia took Pskov following a swift advance, and reached the neighborhood of Luga and Novgorod, within operational reach of Leningrad. But it was stopped by fierce resistance south of the city. However, the 18th Army with some 350,000 men lagged behind — forcing its way to Ostrov and Pskov after the Soviet troops of the Northwestern Front retreated towards Leningrad. On 10 July both Ostrov and Pskov were captured and the 18th Army reached Narva and Kingisepp, from where advance toward Leningrad continued from the Luga River line. This had the effect of creating siege positions from the Gulf of Finland to Lake Ladoga, with the eventual aim of isolating Leningrad from all directions. The Finnish Army was then expected to advance along the eastern shore of Lake Ladoga.[19]

Orders of battle

Coral up to Jul 9. Pink up to Sep 1. Green up to Dec 5.

Germany

- Army Group North (Field Marshal von Leeb)[20]

- 18th Army (von Küchler)

- XXXXII Corps (2 infantry divisions)

- XXVI Corps (3 inf divisions)

- 16th Army (Busch)

- XXVIII Corps (2 inf, 1 armored divisions)

- I Corps (2 infantry divisions)

- X Corps (3 infantry divisions)

- II Corps (3 infantry divisions)

- (L Corps — Under 9. Army) (2 inf divisions)

- 4th Panzergruppe (Hoepner)

- XXXVIII Corps (1 infantry division)

- XXXXI Motorized Corps (Reinhard) (1 infantry, 1 motorized, 1 armored divisions)

- LVI Motorized Corps (von Manstain) (1 infantry, 1 mot, 1 arm, 1 panzergrenadier divisions)

- 18th Army (von Küchler)

Finland

- Finnish Defence Forces HQ (Marshal of Finland Mannerheim)[21]

- I Corps (2 infantry divisions)

- II Corps (2 inf divisions)

- IV Corps (3 inf divisions)

Soviet Union

- Northern Front (Lieutenant General Popov)[22]

- 7th Army (2 rifle, 1 militia divisions, 1 marine brigade, 3 motorized rifle and 1 armored regiments)

- 8th Army

- X Rifle Corps (2 rifle divisions)

- XI Rifle Corps (3 rifle divisions)

- Separate Units (3 rifle divisions)

- 14th Army

- XXXXII Rifle Corps (2 rifle divisions)

- Separate Units (2 rifle divisions, 1 Fortified area, 1 motorized rifle regiment)

- 23rd Army

- XIX Rifle Corps (3 rifle divisions)

- Separate Units (2 rifle, 1 mot divisions, 2 Fortified areas, 1 rifle regiment)

- Luga Operation group

- XXXXI Rifle Corps (3 rifle divisions)

- Separate Units (1 armored brigade, 1 rifle regiment)

- Kingisepp Operation Group

- Separate Units (2 rifle, 2 militia, 1 armored divisions, 1 Fortified area)

- Separate Units (3 rifle divisions, 4 guard militia divisions, 3 Fortified areas, 1 rifle brigade)

From these, 14th Army defended Murmansk and 7th Army defended Ladoga Karelia; thus they did not participate in the initial stages of the siege. 8th Army was initially part of the Northwestern Front and retreated through the Baltics. (8th army was transferred to Northern Front on July 14).

At 23 August the Northern front was divided to Leningrad front and Karelian front, as it become impossible for front HQ to control everything between Murmansk and Leningrad.

Severing lines of communication

On 6 August Hitler repeated his order: "Leningrad first, Donetsk Basin second, Moscow third."[23] From August 1941 to January 1944 anything that happened between the Arctic Ocean and Lake Ilmen concerned the Wehrmacht's Leningrad siege operations.[5] Arctic convoys using the Northern Sea Route delivered American Lend-Lease food and war material supplies to the Murmansk railhead (although the rail link to Leningrad became cut by Finnish armies just north of the city); and also supplies to several other locations in Lapland.

Encirclement of Leningrad

Finnish intelligence was particularly helpful for Hitler, as the Finns had broken some of the Soviet military codes and were able to read their low-level correspondence.[24] He constantly requested intelligence information about Leningrad.[5] Finland's role in Operation Barbarossa was laid out in Hitler's Directive 21, "The mass of the Finnish army will have the task, in accordance with the advance made by the northern wing of the German armies, of tying up maximum Russian strength by attacking to the west, or on both sides, of Lake Ladoga".[25] The last rail connection to Leningrad was severed on August 30, when Germans reached the Neva River. On September 8, the last land connection to the besieged city was severed when the Germans reached Lake Ladoga at Orekhovets. Bombing on September 8 caused 178 fires.[26] Hitler's directive on October 7, signed by Alfred Jodl was a reminder not to accept capitulation.[27]

Finland and Germany

By August 1941, the Finns had advanced within 20 km of the northern suburbs of Leningrad, threatening the city from the north, and were also advancing through Karelia, east of Lake Ladoga, threatening the city from the east. However, Finnish forces halted their advance several kilometers away from the suburbs of Leningrad at the old Soviet-Finnish border on the Karelian Isthmus.[28] For next three years, the Finns did little or nothing to contribute to the battle for Leningrad.[29] The Finnish headquarters rejected German pleas for aerial attacks against Leningrad[30] and did not advance farther south from the River Svir in the occupied East Karelia (160 kilometers northeast of Leningrad), which they reached on September 7. In the southeast, Germans captured Tikhvin on November 8, but failed to complete the encirclement of Leningrad by advancing further north to join with the Finns at the Svir River. A month later, on December 9 a counter-attack of the Volkhov Front forced the Wehrmacht to retreat from the Tikhvin positions to the River Volkhov line.[2][5]

6 September 1941, Germany's Chief of Staff Alfred Jodl visited Helsinki. Jodl's main reason for coming to Helsinki was to persuade Mannerheim to continue the Finnish offensive. During 1941 Finnish President Ryti declared in numerous speeches to the Finnish Parliament that the aim of the war was to regain territories lost during the Winter War and gain more territories in the east to create a "Greater Finland"[31][32][33] After the war Ryti stated: "On August 24, 1941 I visited the headquarters of Marshal Mannerheim. The Germans aimed us at crossing the old border and continuing the offensive to Leningrad. I said that the capture of Leningrad was not our goal and that we should not take part in it. Mannerheim and the military minister Walden agreed with me and refused the offers of the Germans. The result was a paradoxical situation: the Germans could not approach Leningrad from the north..." In fact the German and Finnish armies maintained the siege together until January 1944, but there was little, or no systematic shelling or bombing from the Finnish positions.[14]

The proximity of the Finnish army's positions - 33-35 kilometers from the center of Leningrad — and the threat of a Finnish attack complicated the defense of the city. At one point the Front Commander Popov could not release reserves facing the Finnish Army for deployment against the Wehrmacht because they were needed to bolster the 23rd Army's defence on the Karelian Isthmus.[34] On August 31, 1941 Mannerheim ordered a stop to the offensive when the Finnish advance reached the 1939 border at the shores of the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga, after which Finnish offensives only continued by way of reducing the salients of Beloostrov and Kirjasalo,[35] which threatened Finnish positions at the coast of the Gulf of Finland and south of river Vuoksi respectively.[35]

As the Finns reached the line during the first days of September, Popov experienced a reduction in pressure on Red Army forces, allowing him to transfer two divisions to the German sector on September 5.[36] However, in November 1941, according to Soviet sources Finns made another advance towards Leningrad and crossed the Sestra River, but were stopped again at the Sestroretsk and Beloostrov settlements 20–25 km north of Leningrad's outer suburbs.[14][37] There is no information in Finnish sources of such an offensive and neither do Finnish casualty reports indicate any excess casualties at the time.[38] On the other hand, Soviet forces captured the so-called "Munakukkula" hill one kilometer west from Lake Lempaala in the evening of November 8, but Finns recaptured it next morning.[39] Later, in the summer of 1942, a special Naval Detachment K was formed from Finnish, German and Italian naval units to patrol the waters of Lake Ladoga. It made an unsuccessful operation to cut the Leningrad supply route on southern Ladoga.[14][24][40] The idea of the operation was presented to Germans by the Finnish Lieutenant General Paavo Talvela.[41]

Defensive operations

Initial defence of Leningrad was undertaken by the troops of the Leningrad Front commanded by Marshal Kliment Voroshilov which included the 23rd Army in the northern sector between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga, and the 48th Army (Soviet Union) occupying the western sector between Gulf of Finland and the Slutsk-Mga position. Also in the Front were the Leningrad Fortified Region, the Leningrad garrison, the Baltic Fleet forces, and the Koporsk, Southern and Slutsk-Kolpin operational groups.

Defense of civilian evacuees

By September 1941 the link with the Volkhov Front (commanded by Kirill Meretskov) was severed and the defensive sectors were held by four armies: 23rd Army in the northern sector, 42rd Army on the western sector, 55th Army on the southern sector, and the 67th Army on the eastern sector. The 8th Army of the Volkhov Front had the responsibility of maintaining the logistic route to the city in coordination with the Ladoga Flotilla. Air cover for the city was provided by the Leningrad military district PVO Corps and Baltic Fleet naval aviation units.

The defense operation to protect the 1,400,000 civilian evacuees was part of the Leningrad counter-siege operations, and was carried under the command of Andrei Zhdanov, Kliment Voroshilov, and Aleksei Kuznetsov. Additional military operations were carried in coordination with the Baltic Fleet naval forces under the general command of Admiral Vladimir Tributs. Major military involvement in helping evacuation of the civilians was carried by the Ladoga Flotilla under the command of V. Baranovsky, S.V. Zemlyanichenko, P.A. Traynin, and B.V. Khoroshikhin.

Bombardment

By September 8, 1941 German forces had largely surrounded the city, cutting off all supply routes to Leningrad and its suburbs. Unable to press home their offensive, and facing defenses of the city organized by Marshal Zhukov, the Axis armies laid siege to the city for 872 days.

Artillery bombardments of Leningrad began in August 1941, increasing in intensity during 1942 with the arrival of new equipment. It was stepped up further during 1943, when several times as many shells and bombs were used as in the year before. Torpedoes were often used for night bombings by the Luftwaffe. Against this, the Soviet Baltic Fleet Navy aviation made over 100,000 air missions to support their military operations during the siege.[42] German shelling and bombings killed 5,723 and wounded 20,507 civilians in Leningrad during the siege.[43]

Supplying the defenders

To sustain the defense of the city it was vitally important for the Red Army to establish a route for bringing constant supplies into Leningrad. This route was effected over the southern part of Lake Ladoga, by means of watercraft during the warmer months and land vehicles driven over thick ice in the winter. The security of the supply route was ensured by the Ladoga Flotilla, the Leningrad PVO Corps, and route security troops. The route would also be used to evacuate civilians from the besieged city. This was because no evacuation plan had been made available in the chaos of the first winter of the war, and the city literally starved in complete isolation until November 20, 1941 when the ice road over Lake Ladoga became operational.

This road was named the Road of Life (Russian: Дорога жизни). As a road it was very dangerous. There was the risk of vehicles becoming stuck in the snow or sinking through broken ice caused by the constant German bombardment. Because of the high winter death toll the route also became known as the "Road of Death". However, the lifeline did bring military and food supplies in and took civilians out, allowing the city to continue resisting the enemy.

Effect on the city

The two-and-a-half year siege caused the greatest destruction and the largest loss of life ever known in a modern city.[14] On Hitler's express orders, most of the palaces of the Tsars, such as the Catherine Palace, Peterhof Palace, Ropsha, Strelna, Gatchina, and other historic landmarks located outside the city's defensive perimeter were looted and then destroyed, with many art collections transported to Nazi Germany.[44] A number of factories, schools, hospitals and other civil infrastructure were destroyed by air raids and long range artillery bombardment.

The 872 days of the siege caused unparalleled famine in the Leningrad region through disruption of utilities, water, energy and food supplies. This resulted in the deaths of up to 1,500,000[45] soldiers and civilians and the evacuation of 1,400,000 more, mainly women and children, many of whom died during evacuation due to starvation and bombardment.[1][2][5] Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery alone in Leningrad holds half a million civilian victims of the siege. Economic destruction and human losses in Leningrad on both sides exceeded those of the Battle of Stalingrad, the Battle of Moscow, or the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The siege of Leningrad is the most lethal siege in world history, and some historians speak of the siege operations in terms of genocide, as a "racially motivated starvation policy" that became an integral part of the unprecedented German war of extermination against populations of the Soviet Union generally.[46][47]

Civilians in the city suffered from extreme starvation, especially in winter of 1941–1942. For example, from November 1941 to February 1942 the only food available to the citizen was 125 grams of bread, which by 50–60 per cent consisted of sawdust and other inedible admixtures, and distributed with ration cards. For about 2 weeks at the beginning of January 1942 even this food was available only for workers and military personnel. In conditions of extreme temperatures (down to −30 °С) and city transport being out of service a few kilometers to the food distributing kiosks were insurmountable obstacles for many citizens. In January-February 1942 about 700–10,000 citizens died every day, most of them from hunger. People often died on the streets, and citizens shortly became accustomed to look of death.

Reports of cannibalism appeared in the winter of 1941-1942, after all birds, rats and pets were eaten by survivors.[48] Hungry gangs attacked and ate defenseless people.[49] Leningrad police even formed a special unit to combat cannibalism.[50]

Soviet relief of the siege

Sinyavin Offensive

The Sinyavin Offensive was a Soviet attempt to break the blockade of the city in early autumn 1942. The 2nd Shock and the 8th armies were to link up with the forces of the Leningrad Front. At the same time the German side was preparing an offensive Operation Nordlicht to capture the city, using the troops freed up after the capture of Sevastopol.[51] Neither side was aware of the other's intentions until the battle started.

The Sinyavin offensive started on the 27th August 1942, with some small-scale attacks by the Leningrad front on the 19th, pre-empting "Nordlicht" by a few weeks. The successful start of the operation forced the German to redirect troops from the planned "Nordlicht" to counterattack the Soviet armies. The counteroffensive saw the first deployment of the Tiger tank, though with limited success. After parts of the 2nd strike army were encircled and destroyed, the Soviet offensive was halted. However the German forces had to abandon their offensive on Leningrad as well.

Operation Iskra

The encirclement was broken in the wake of Operation Iskra - (English: Operation Spark) - a full-scale offensive conducted by the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts. This offensive started in the morning of January 12, 1943. After fierce battles the Red Army units overcame the powerful German fortifications to the south of Lake Ladoga, and on January 18, 1943 the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts met, opening a 10–12 km wide land corridor, which could provide some relief to the besieged population of Leningrad.

Lifting the siege

The siege continued until January 27, 1944, when the Soviet Leningrad-Novgorod Strategic Offensive expelled German forces from the southern outskirts of the city. This was a combined effort by the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts, along with the 1st and 2nd Baltic Fronts. The Baltic Fleet provided 30% of aviation power for the final strike against the Wehrmacht.[42] In the summer of 1944, the Finnish Defence Forces were pushed back to the other side of the Bay of Vyborg and the Vuoksi River.

Timeline

1941

- April: Hitler intends to occupy and then destroy Leningrad, according to plan Barbarossa and Generalplan Ost[52]

- June 22: The Axis powers' invasion of Soviet Union begins with Operation Barbarossa.

- June 23: Leningrad commander M. Popov, sends his second in command to reconnoiter defensive positions south of Leningrad.[53]

- June 29: Construction of the Luga-line defense fortifications begins[54] together with evacuation of children and women.

- June–July: Over 300 thousand civilian refugees from Pskov and Novgorod escaping from the advancing Germans come to Leningrad for shelter. The armies of the North-Western Front join the front lines at Leningrad. Total military strength with reserves and volunteers reaches 2 million men involved on all sides of the emerging battle.

- July 19–23: First attack on Leningrad by Army Group North is stopped 100 km south of the city.

- July 27: Hitler visits Army Group North, angry at the delay. He orders Field Marshal von Leeb to take Leningrad by December.[52]

- July 31: Finns attack the Soviet 23rd Army at the Karelian Isthmus, eventually reaching northern pre-Winter War Finnish-Soviet border.

- August 20 – September 8: Artillery bombardments of Leningrad hit industries, schools, hospitals, and civilian houses.

- August 21: Hitler's Directive No.34 orders "Encirclement of Leningrad in conjunction with the Finns."[55]

- August 20 – 27: Evacuation of civilians is blocked by attacks on railroads and other exits from Leningrad.[56]

- August 31: Finnish forces go on the defensive and straighten their front line.[28] This involves crossing the 1939 pre-Winter War border and occupation of municipalities of Kirjasalo and Beloostrov.[28]

- September 6: German High Command's Alfred Jodl fails to persuade Finns to continue offensive against Leningrad.[30]

- September 2–9: Finns capture the Beloostrov and Kirjasalo salients and conduct defensive preparations.[35][37]

- September 8: Land encirclement of Leningrad is completed when the German forces reach the shores of Lake Ladoga.[14][52]

- September 10: Joseph Stalin appoints General Zhukov to replace Marshal Voroshilov as Leningrad Front commander.[57]

- September 12: The largest food depot in Leningrad, the Badajevski General Store, is destroyed by a German bomb.[58]

- September 15: von Leeb has to remove the 4th Panzergruppe from the front lines and transfer it to Army Group Center for the Moscow offensive.[59]

- September 19: German troops are stopped 10 km from Leningrad. Citizens join the fighting at the defense lines.

- September 22: Hitler directs that "Saint Petersburg must be erased from the face of the Earth".[60]

- September 22: Hitler declares, "....we have no interest in saving lives of the civilian population."[60]

- November 8: Hitler states in a speech at Munich: "Leningrad must die of starvation."[14]

- November 10: Soviet counter-attack begins, forcing Germans to retreat from Tikhvin back to the Volkhov River by December 30, preventing them from joining Finnish forces stationed at the Svir River east of Leningrad.[61]

- December: Winston Churchill wrote in his diary "Leningrad is encircled, but not taken."[62]

- December 6 Great Britain declared war on Finland. This was followed by declaration of war from Canada, Australia, India and New Zealand.[63]

1942

- January 7: Soviet Lyuban Offensive is launched; it lasts 16 weeks and is unsuccessful, resulting in the loss of the 2nd Shock Army.

- January: Soviets launch battle for the Nevsky Pyatachok bridgehead in an attempt to break the siege. This battle lasts until May 1943, but is only partially successful. Very heavy casualties experienced by both sides.

- April 4–30: Luftwaffe operation Eis Stoß (Ice impact) fails to sink Baltic Fleet ships iced in at Leningrad.[64]

- June–September: New German artillery bombards Leningrad with 800 kg shells.

- August: The Spanish Blue Division (División Azul) transferred to Leningrad.

- August 14 – October 27 : Naval Detachment K clashes with Leningrad supply route on Lake Ladoga.[14][24][40]

- August 19: Soviets begin a 8 week long Sinyavin relief offensive, which fails to lift the siege, but thwarts German offensive plans (Nordlicht).[65]

1943

- January–December: Increased artillery bombardments of Leningrad.

- January 12 – January 30: Operation Iskra penetrates the siege by opening a land corridor along the coast of Lake Ladoga into the city.

1944

- January 14 - March 1: Several Soviet offensive operations begin, aimed at ending the siege.

- January 27: Siege of Leningrad ends. Germans forces pushed 60–100 km away from the city.

- January: Before retreating the German armies loot and destroy the historical Palaces of the Tsars, such as the Catherine Palace, Peterhof Palace, the Gatchina, and the Strelna. Many other historic landmarks and homes in the suburbs of St. Petersburg are looted and then destroyed, and a large number of valuable art collections is moved to Nazi Germany.

- During the siege, 3200 residential buildings, 9000 wooden houses (burned), 840 factories and plants were destroyed in Leningrad and suburbs.[66]

Additional notes

Controversy over Finnish participation

Almost all historians regard the siege as a German operation and do not consider that the Finns effectively participated in the siege. Russian historian Nikolai Baryshnikov argues that active Finnish participation did occur, but historians have been mostly silent about it most likely due to the friendly nature of post-war Soviet-Finnish relations.[67] The main issues which count in favor of the former view are: (a) the Finns stayed at the pre-Winter War border at the Karelian Isthmus, despite German wishes and requests, and (b) they did not bombard the city from planes or with artillery and did not allow the Germans to bring their own land forces to Finnish lines. Baryshnikov explains that the Finnish military in the region strategically depended on the Germans, and it lacked the required means and will to press the attack against Leningrad any further.[68]

Monument to the 'Road of Life'

On October 29, 1966 a monument to the Road of Life was erected. Entitled 'Broken Ring,' designed and created by Konstantin Simun, this monument pays tribute not only to the lives saved via the frozen Ladoga, but also the many lives broken by the blockade.

The monument is a huge bronze ring with a gap in it, pointing towards the site that the Russians eventually broke through the encircling German forces. The German bunker they captured is preserved as a momento opposite the break.

In the centre a Russian mother cradles her dying soldier son. It is customary for newlyweds to come here to give thanks to the fallen. Whilst being sited in the centre of a roundabout it is easily accessed.

The monument implies that the siege lasted 900 days.

Deportation of Local Civilians During the Siege

Although Leningrad was under Siege, the local administration found opportunities to deport local unwanted ethnicities from Leningrad Area to Siberia in March 1942.[69] For that, the 'Road of Life' was used. According to Eino Puhilas, a local Finn, who was deported in 1942 as a child from a village near Leningrad, the deportation was carried out by Soviet military, who gave local Finns (but not Russians) the order to come to a nearby road and take along some clothes and household items. Thereafter the deportees were transported to the shore of Lake Ladoga and from there, over the lake in unlighed trucks under enemy fire, to Siberia.

See also

- Operation Barbarossa

- Eastern Front (World War II)

- Adolf Hitler

- Mannerheim

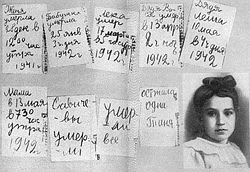

- Tanya Savicheva

- World War II casualties

- Naval Detachment K

- List of famines

- Blue Division (División Azul)

- Effect of the Siege of Leningrad on the city

- Consequences of German Nazism

- Hero-City Obelisk

- Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery

- Lake Ladoga

- Nevsky Pyatachok

- Leningrad Affair

Bibliography

- Barber, John; Dzeniskevich, Andrei (2005), Life and Death in Besieged Leningrad, 1941–44, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, ISBN 1-4039-0142-2

- Baryshnikov, N.I. (2003), Блокада Ленинграда и Финляндия 1941–44 (Finland and the Siege of Leningrad), Институт Йохана Бекмана

- Glantz, David (2001), The Siege of Leningrad 1941–44: 900 Days of Terror, Zenith Press, Osceola, WI, ISBN 0-7603-0941-8

- Goure, Leon (1981), The Siege of Leningrad, Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, CA, ISBN 0-8047-0115-6

- Granin, Daniil Alexandrovich (2007), Leningrad Under Siege, Pen and Sword Books Ltd, ISBN 9781844154586, http://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/?product_id=1502

- Kirschenbaum, Lisa (2006), The Legacy of the Siege of Leningrad, 1941–1995: Myth, Memories, and Monuments, Cambridge University Press, New York, ISBN ISBN 0-521-86326-0

- Klaas, Eva (2010), A Deportee Published His Memories in Book, Virumaa Teataja, http://www.virumaateataja.ee/?id=286756

- Lubbeck, William; Hurt, David B. (2006), At Leningrad's Gates: The Story of a Soldier with Army Group North, Pen and Sword Books Ltd, ISBN 9781844156177, http://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/?product_id=1457

- Platonov, S.P. ed. (1964), Bitva za Leningrad, Voenizdat Ministerstva oborony SSSR, Moscow

- Salisbury, Harrison Evans (1969), The 900 Days: The Siege of Leningrad, Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-81298-3

- Simmons, Cynthia; Perlina, Nina (2005), Writing the Siege of Leningrad. Women's diaries, Memories, and Documentary Prose, University of Pittsburgh Press, ISBN 9780822958697

- Willmott, H.P.; Cross, Robin; Messenger, Charles (2004), The Siege of Leningrad in World War II, Dorling Kindersley, ISBN 978-0-7566-2968-7

- Wykes, Alan (1972), The Siege of Leningrad, Ballantines Illustrated History of WWII

References

- Backlund, L.S. (1983), Nazi Germany and Finland, University of Pennsylvania. University Microfilms International A. Bell & Howell Information Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

- Baryshnikov, N.I.; Baryshnikov, V.N. (1997), Terijoen hallitus, TPH

- Baryshnikov, N.I.; Baryshnikov, V.N.; Fedorov, V.G. (1989), Finlandia vo vtoroi mirivoi voine (Finland in the Second World War), Lenizdat, Leningrad

- Baryshnikov, N.I.; Manninen, Ohto (1997), Sodan aattona, TPH

- Baryshnikov, V.N. (1997), Neuvostoliiton Suomen suhteiden kehitys sotaa edeltaneella kaudella, TPH

- Bethel, Nicholas; Alexandria, Virginia (1981), Russia Besieged, Time-Life Books, 4th Printing, Revised

- Brinkley, Douglas; Haskey, Mickael E. (2004), The World War II. Desk Reference, Grand Central Press

- Carell, Paul (1963), Unternehmen Barbarossa — Der Marsch nach Russland

- Carell, Paul (1966), Verbrannte Erde: Schlacht zwischen Wolga und Weichsel (Scorched Earth: The Russian-German War 1943-1944), Verlag Ullstein GmbH, (Schiffer Publishing), ISBN 0-88740-598-3

- Cartier, Raymond (1977), Der Zweite Weltkrieg (The Second World War), R. Piper & CO. Verlag, München, Zürich

- Churchill, Winston S., Memoires of the Second World War. An abridgment of the six volumes of The Second World War, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, ISBN 0-395-59968-7

- Clark, Alan (1965), Barbarossa. The Russian-German Conflict 1941-1945, Perennial, ISBN 0-688-04268-6

- Fugate, Bryan I. (1984), Operation Barbarossa. Strategy and Tactics on the Eastern Front, 1941, Presidio Press, ISBN 0891411976, ISBN 978-0-89141-197-0

- Ganzenmüller, Jörg (2005), Das belagerte Leningrad 1941-1944, Ferdinand Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn, ISBN 350672889X

- Гречанюк, Н. М.; Дмитриев, В. И.; Корниенко, А. И. (1990), Дважды, Краснознаменный Балтийский Флот (Baltic Fleet), Воениздат

- Higgins, Trumbull (1966), Hitler and Russia, The Macmillan Company

- Jokipii, Mauno (1987), Jatkosodan synty (Birth of the Continuation War), ISBN 951-1-08799-1

- Juutilainen, Antti; Leskinen, Jari (2005), Jatkosodan pikkujättiläinen, Helsinki

- Kay, Alex J. (2006), Exploitation, Resettlement, Mass Murder. Political and Economic Planning for German Occupation Policy in the Soviet Union, 1940 - 1941, Berghahn Books, New York, Oxford

- Miller, Donald L. (2006), The story of World War II, Simon $ Schuster, ISBN 0-74322718-2

- National Defence College (1994), Jatkosodan historia 1-6, Porvoo, ISBN 951-0-15332-X

- Seppinen, Ilkka (1983), Suomen ulkomaankaupan ehdot 1939-1940 (Conditions of Finnish foreign trade 1939-1940), ISBN 951-9254-48-X

- Симонов, Константин (1979), Записи бесед с Г. К. Жуковым 1965–1966, Hrono, http://www.hrono.ru/dokum/197_dok/1979zhukov2.html

- Suvorov, Victor (2005), I take my words back, Poznań, ISBN 83-7301-900-X

- Vehviläinen, Olli; McAlister, Gerard (2002), Finland in the Second World War: Between Germany and Russia, Palgrave

External links

| the Siege of Leningrad | |

|---|---|

| Russian map of the operations around Leningrad in 1943 Blue are the German and co-belligerent Finnish troops. The Soviets are red.[70] | |

| map of the advance on Leningrad and relief Blue are the German and co-belligerent Finnish troops. The Soviets are red.[71] | |

- (Youtube) Leningrad blockade part1 (Retrieved on June 29, 2008)

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Brinkley 2004, p. 210

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Wykes 1972, pp. 9-21

- ↑ Siege of Leningrad. Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Baryshnikov 2003; Juutilainen 2005, p. 670; Ekman, P-O: Tysk-italiensk gästspel på Ladoga 1942, Tidskrift i Sjöväsendet 1973 Jan.–Feb., pp. 5–46.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Carell 1966, pp. 205-210

- ↑ Salisbury 1969, p. 331

- ↑ Сведения городской комиссии по установлению и расследованию злодеяний немецко-фашистских захватчиков и их сообщников о числе погибшего в Ленинграде населения ЦГА СПб, Ф.8357. Оп.6. Д. 1108 Л. 46-47

- ↑ The Siege of Leningrad, 1941 - 1944

- ↑ Carell 1963

- ↑ By 1939 the city was responsible for 11% of all Soviet industrial output. (Encyclopedia Britannica. Saint Petersburg, Vol 26, p 1044. 15th edition, 1997)

- ↑ Orchestral manoeuvres (part one). From the Observer

- ↑ Carell 1966, pp. 205-240

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Carell 1966, pp. 205-208

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 Baryshnikov 2003

- ↑ Higgins 1966

- ↑ Brinkley 2004, pp. 210

- ↑ Miller 2006, pp. 67

- ↑ Willmott 2004

- ↑ Хомяков, И (2006) (in Russian). История 24-й танковой дивизии ркка. Санкт-Петербург: BODlib. pp. 232 с. http://www.soldat.ru/force/sssr/24td/24td-4.html.

- ↑ Glantz 2001, p. 367

- ↑ National Defence College 1994, pp. 2:194,256

- ↑ Glantz 2001, p. 351

- ↑ Higgins 1966, pp. 151

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Juutilainen 2005, pp. 187-9

- ↑ Führer Directive 21. Operation Barbarossa

- ↑ "St Petersburg - Leningrad in the Second World War" 9th May 2000. Exhibition. The Russian Embassy. London

- ↑ "Nuremberg Trial Proceedings Vol. 8", from The Avalon Project at Yale Law School

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 National Defence College 1994, p. 2:261

- ↑ Glantz 2001, pp. 166

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 National Defence College 1994, p. 2:260

- ↑ Vehviläinen 2002

- ↑ Пыхалов, И (2003). "«великая оболганная война»". Военная литература. Со сслылкой на Барышников В.Н.Вступление Финляндии во Вторую мировую войну. 1940-1941 гг. СПб. Militera. pp. с. 28. http://militera.lib.ru/research/pyhalov_i/11.html. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ↑ "«и вновь продолжается бой...»". Андрей Сомов. Центр Политических и Социальных Исследований Республики Карелия.. Politika-Karelia. 2003-01-28. http://politika-karelia.ru/shtml/article.shtml?id=16. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ↑ Glantz 2001, pp. 33–34

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 National Defence College 1994, pp. 2:262-267

- ↑ Platonov 1964

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Approaching Leningrad from the North. Finland in WWII (На северных подступах к Ленинграду)" (in Russian). http://www.aroundspb.ru/finnish/saveljev/war1941.php.

- ↑ "Database of Finns killed in WWII". War Archive. Finnish National Archive. http://kronos.narc.fi/menehtyneet/.

- ↑ National Defence College 1994, p. 4:196

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Ekman, P-O: Tysk-italiensk gästspel på Ladoga 1942, Tidskrift i Sjöväsendet 1973 Jan.–Feb., pp. 5–46.

- ↑ YLE: Kenraali Talvelan sota (in Finnish)

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Гречанюк 1990

- ↑ Glantz 2001, p. 130

- ↑ Nicholas, Lynn H. (1995). The Rape of Europa: the Fate of Europe's Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War. Vintage Books

- ↑ Salisbury 1969, pp. 590f

- ↑ Ganzenmüller 2005, pp. 17,20

- ↑ Barber 2005

- ↑ 900-Day Siege of Leningrad

- ↑ PBS World War 2 Retrieved on March 30, 2010.

- ↑ This Day in History 1941: Siege of Leningrad begins

- ↑ E. Manstein. Lost victories. Ch 10

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Cartier 1977

- ↑ Glantz 2001, p. 31

- ↑ Glantz 2001, p. 42

- ↑ Higgins 1966, pp. 156

- ↑ The World War II. Desk Reference. Eisenhower Center director Douglas Brinkley. Editor Mickael E. Haskey. Grand Central Press, 2004. Page 8.

- ↑ Glantz 2001, p. 64

- ↑ Glantz 2001, p. 114

- ↑ Glantz 2001, p. 71

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Hitler, Adolf (1941-09-22). "Directive No. 1601" (in Russian). http://www.hrono.ru/dokum/194_dok/19410922.html.

- ↑ Carell 1966, pp. 210

- ↑ Churchill, Winston (2000) [1950]. The Second World War (The Folio Society ed.). London: Cassel & Co. pp. Volume III, pp..

- ↑ pp.98-105, Finland in the Second World War, Bergharhn Books, 2006

- ↑ Bernstein, AI; Бернштейн, АИ (1983). "Notes of aviation engineer (Аэростаты над Ленинградом. Записки инженера — воздухоплавателя. Химия и Жизнь №5)" (in Russian). pp. с. 8–16. http://xarhive.narod.ru/Online/hist/anl.html.

- ↑ Glantz 2001, pp. 167-173

- ↑ Siege of 1941-1944

- ↑ Baryshnikov 2003, p. 3

- ↑ Baryshnikov 2003, p. 82

- ↑ Klaas 2010

- ↑ "ОТЕЧЕСТВЕННАЯ ИСТОРИЯ. Тема 8". Ido.edu.ru. http://www.ido.edu.ru/ffec/hist/h8.html. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ↑ "ИТАР-ТАСС :: 60 ЛЕТ ВЕЛИКОЙ ПОБЕДЕ ::" (in (Russian)). Victory.tass-online.ru. http://victory.tass-online.ru/?page=gallery&gcid=9. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||